The Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark in Birmingham, AL, is home to SLSF #4018, a 1919 Lima built Mikado

(2-8-2) type locomotive, but the site itself is a fascinating place to visit. It was connected to railroads not just physically by the delivery of raw materials and shipping out of pig iron, but also through investment and ownership by some key figures in the development of Southern railroads.

Overall, the site powerfully attests to a peculiarly Southern version of the economic and social impacts of industrialisation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the eventual decline of American heavy industry.

Located beside the 1st Ave N overpass close to downtown Birmingham (the entrance is at the corner of 2nd Ave N and 32nd St N), the museum is open Tues-Sat 10.00am-4.00pm and Sunday 12.00pm-4.00pm. The visitor centre, just out of view on the left in the photo above, is in what once housed an electrical repair shop and a bath house for the furnace workers.

The equipment at the museum is much what was left when the furnaces last operated in 1970, mostly reflecting modernisation undertaken between 1921 and 1931.

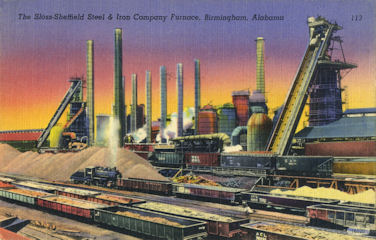

Above, a postcard from the 1930s shows the proximity of the Sloss-Sheffield complex to downtown Birmingham: the double spired red brick building upper-right is the city's main passenger depot, Birmingham Terminal Station. Built in 1909, the depot was demolished in 1969. The postcard also shows the extent of railroad activity surrounding the furnaces.

Below, another postcard from the 1930s, based on a black and white photograph taken from the east, shows the company's marshalling yard, the skip trestles and furnace complex.

Below, a postcard from the 1900s showing cast iron pigs outside the pig casting shed.

The first furnace on the site was begun in 1880 by Colonel James Withers Sloss, a proponent of Alabama's post Civil War industrialisation and, as president of the Nashville & Decatur Railroad, crucially allied to the Louisville & Nashville. Seeking an outlet south to the Gulf, the L&N set preferential freight rates, forged alliances and agreed loans to further its aims. As part of this effort, it invested $80,000, 26% of the $300,000 capitalisation, for the Sloss Furnace Company in 1881.

Above, a postcard from the 1900s showing pigs ready for loading onto rail cars and, below, another 1900s postcard showing the yard from a different angle. Note the locomotive switching.

The growth of railroads was a key driver of the South's industrialisation, as it was in the rest of the US, and contributed to Alabama's emergence as a producer of coal and iron. By the 1900s, with furnaces in north Birmingham and extensive mining operations in northern Alabama, Sloss-Sheffield had become the second largest pig iron manufacturer in the district.

Sloss sold the furnaces in 1886 to a group of Virginian investors, many of whom had stakes in the Richmond & West Point Terminal Railway and Warehouse Company, owner of a railroad system stretching from Atlanta to the Mississippi.

Among them was John W. Johnson, president of the Georgia Pacific, and John Randolph Bryan who, in 1887, established the Richmond Locomotive Works (later part of Alco). Bryan was a key figure in the new Sloss Iron and Steel Company and dominated it and its successor, Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron, until he died in 1908.

New blowers were installed in 1902 and new boilers in 1906 and 1914, by which time, the company was one of the largest producers of pig iron in the world.

After WWI, Sloss-Sheffield began a process of modernisation costing $625,000 under Hugh Morrow, appointed Vice President in 1919 and President in 1920. In 1927, the No.2 furnace was completely rebuilt, followed by the No.1 furnace in 1928-29. New skip hoists were installed as well as additional blower engines and an automatic pig casting machine in 1931.

During WWII, the company was a major contributor to the war effort. Large volumes of its cast iron were used to make marine engines, bombs, mortars and hand grenades: about 60% of all hand grenades used by US forces during the war were manufactured from Birmingham cast iron.

In 1942, US Pipe and Foundry had gained control of Sloss-Sheffield and the companies merged in 1952, but the industry already faced competition from low cost foreign imports and technological change.

Sold to the Jim Walter Corporation in 1969, the furnaces closed in 1971 when the land was donated to the Alabama State Fair Authority for possible development as a museum of industry. Plans to demolish the furnaces met considerable local opposition, however, and the site went on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Then, in 1977, the city made a $3.3 million bond issue to preserve the site, which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1981. The museum opened in 1983.

Thirty-eight USRA "light" Mikados were assigned to PRR, but thirty-three were rejected. The USRA re-assigned the cast-offs to the Missouri Pacific (#4000-#4007) and SLSF (#4017-#4031), and ten more came to SLSF from the Indiana Harbor Belt Line (#4008-#4016 & #4032).

Initially resistant to the 2-8-2 type, SLSF now found itself with thirty-three of them! Within a few years, however, it had bought a further eighty-five and, from 1943 to 1946, actually converted seven 2-8-0s to 2-8-2s (you can see one of them on the SLSF #1355 page of this website).

#4018 was built by Lima in 1919 for the Pennsylvania Railroad to a standardised United States Railroad Administration (2-8-2) "light" Mikado design. It was one of what were called "war babies", locomotives ordered to build cargo carrying capacity for the country's WWI war effort (you can see the first locomotive built under the USRA regime, BO Q3 #4500, on the B&O Museum Yard & Car Shop page of this website).

Like all the USRA locomotives, however, #4018 arrived too late to help with that work. By the time it was delivered, the war was over.

At the request of then Birmingham Mayor, J. W. Morgan, #4018 was saved from the scrap-yard and donated to the city on 29th May 1952. It travelled on ACL tracks to the Birmingham Fairgrounds where a special spur delivered it to its new display location. A shed was built over it and, in the ensuing years, Frisco employees regularly attended to its condition.

With a major redevelopment of the Fairgrounds planned for 2009, fund-raising began to move #4018 to Sloss Furnaces. The move took place on 19th-21st February 2009.

#4018 is an SLSF Class 4000, weighing 492,400

lbs with 26" x 30" cylinders and 63" drivers. A

coal burner operating at a boiler pressure of

200 psi, it delivered 54,700 lbs tractive effort. The tender has a 10,000 gallon water and 18 tons coal capacity.

#4018 spent much of its life carrying freight between Bessemer and Birmingham, AL. Dieselisation started on the SLSF in the 1950s and steam locomotives were progressively retired, but #4018 was, in fact, the last steam locomotive to operate on any part of the Frisco.

Built by Baldwin in 1948, #30 is the sole surviving switcher rostered by the company. This is an area of inquiry awaiting exploration but, at one time, the roster appears to have included a Whitcomb 45 ton DE27b (#28) built as #104 in 1942 for the US Army's Oak Ordnance Plant in Illiopolis, IL, and two 1951 Baldwin S-8 units (#33 and #34) and two 1952 units (#35 and #36).

Baldwin built one hundred and thirty-nine DS 44-660s at its Eddystone, PA, plant from 1946 to 1949. At 240,000 lbs and 46' long, with a Baldwin 606 NA prime mover powering a Westinghouse WE480 generator to drive four Westinghouse WE362 traction motors, it delivered starting tractive effort of 49,625 lbs at 25% and 34,000 lbs at 6.8 mph with a top speed of 60 mph. #30 is one of only three DS 44-660s to have survived. You can see one of them, CHW #662 on the Virginia Museum of Transportation page of this website.

Above, looking west to the entrance to the company's marshalling yard to the south of the furnaces. The complex was fed with raw materials from the Louisville & Nashville Railroad (now CSX lines).

All the ingredients needed to make iron lay within thirty miles of the furnaces. Huge seams of hematite ran nearly ninety miles through nearby Red Mountain, so called because of the iron ore that stained its faces rust red. To the north and west were deposits of coal, while limestone and dolomite were found locally.

By 1899 when it was reorganised as Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron, the company owned seven blast furnaces including two in the city. It had coal mines in Coalburg, Blossburg, Cardiff, Brazil and Brookside, and ore mines at Irondale and Bessemer. Limestone came from Gate City, and, as the company moved to greater use of brown ore, it opened limonite mines near Leeds on the Cahaba field and then one near Russellville. In 1902, Coalburg was closed and a new coal mine opened at Flat Top.

Above, looking east across the old marshalling yard. The furnaces had connections to the Southern Railway and Alabama Great Southern (both railroads are now part of Norfolk Southern), which facilitated the export of pig iron to other parts of the US and, through the ports of Mobile, AL, to the south and Savannah, GA, to the east, to overseas buyers.

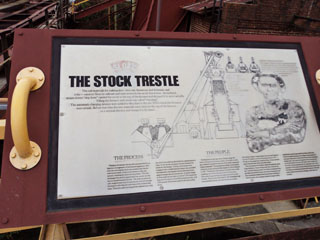

Below, the east end of the elevated stock trestle. Railroad cars were switched onto the trestle up the incline on the far left.

Below, two views along the 800' stock

trestle. The remains of this once bustling feature of the furnace

workings are now warped and mangled, and the two railroad tracks have been removed.

Coal from the company's mines in the Warrior Coal Field west of Birmingham was particularly good for coking but contained impurities that necessitated "washing" before it was coked and shipped to the furnace.

Once switched onto the trestle, the cars appear to have moved backwards and forwards using a system of cables controlled from the west end of the trestle. Doors on the bottom of the cars opened to dump the raw materials, known as "stock", into storage bins below.

In addition to coke and iron ore, the "stock",

stored in separate storage bins, included

limestone and dolomite, substances known as "fluxes". These were essential elements that promoted fluidity in the furnaces and helped remove impurities.

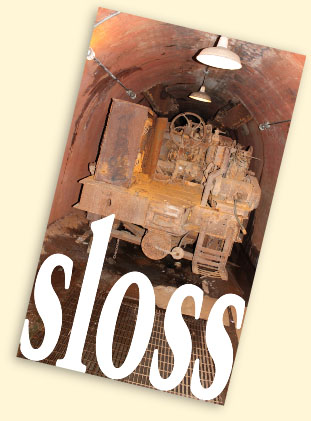

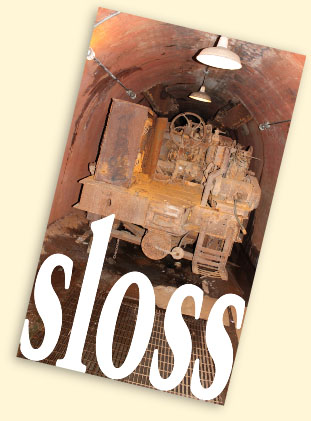

Beneath the storage bins was a 747' long 11' tall charging tunnel constructed in 1927 as part of a modernisation programme. The raw materials were transferred from the bins via chutes to scale cars (the chutes are visible beside the overhead lamps in the photo above). The scale cars weighed the materials in readiness for transfer to skip cars on the skip hoist.

Below, the museum has kept one scale car in the tunnel, as well as another on open air display shown on the right.

Although new furnaces were built at the same time, the two inclined Skip Hoists completed in 1927 and 1929 were perhaps the most visible feature of the modernisation programme.

The hoists each had two skip cars powered by steam driven pulleys to haul raw materials from scale cars in the tunnel below the Stock Trestle to the top of the furnace.

The process was called "charging", and a typical charge consisted of two 3,100 lb skips of coke, two 5,000 lb skips of ore and 1,500 lbs of "fluxes" added to the second ore skip.

Above left, furnace No. 2 and skip hoist from the west end of the Stock Trestle and, above right, from the marshalling yard (No. 2 was not open to the public when I visited). Below left, furnace No. 1 skip hoist from beside the Stock Trestle and, right, from the old marshalling yard.

The old furnaces were charged by hand. Raw materials were loaded into carts and taken to the furnace opening by vertical hoists. Manual filling required skill to ensure proper distribution of the charge so that blasting would proceed evenly, but it was done under great pressure, exposing fillers to the risk of falling into the flaming furnace.

Fillers were also exposed to noxious gases escaping from the stack, so a double bell and hopper on the new furnaces allowed charging without releasing gases.

The skip hoists and furnace top loaders were powered by steam generated by four boilers. Steam from the boilers also powered turbo blowers that supplied the air blast for the furnaces and drove a generator to produce electricity for the plant.

Built in 1902, each 400 hp boiler had five vertical water tubes. Because flames didn't come into contact with the tubes, the boilers could run continuously for long periods without maintenance. They could burn coal and natural gas, but their primary fuel was waste gas from the furnace, the same fuel burned in the Blast Stoves.

Built in 1902, the 3½ storey, red brick, gable roofed blower building is located behind the Furnace No.1 Blast Stoves, so it is difficult to photograph.

It houses two original Allis Chalmers engines and six others built about 1900 and installed second hand in the 1920s. The six 30' tall machines turned 20' flywheels to pump air to the Blast Stoves. Inside the building, temperatures reached 100° F when the blowers were operating. Below, a side view of one of the six blowers.

Below, large pipes carried the hot air from the Blast Stoves to the furnaces.

The two storey brick building bottom was the Pyrometer House. In the upstairs room, it had pyrometers or temperature measuring instruments. Workmen also knew the building as the "dog house" as, if something went wrong with the furnace, they took shelter there for safety. They then said the furnace had "put them in the dog house". The downstairs room was a millwright shop, where furnace repairmen worked.

Other characteristic features of the Sloss skyline are the six cylindrical steel Blast Stoves.

These were lined with heat resistant bricks and an internal lattice of bricks called checkers. Once purified, gases from the furnaces were burned in the stoves to heat the checkers. The gas was then shut off and an air blast blown through the stoves. The checkers heated the air to 1,400° F.

Above, No.1 furnace completed in January 1929 (No.2 was completed in July 1927) operated at 3,600° F. At 82' high and 21' across at the bosh or widest point, it had a daily capacity of 400-450 tons compared to 250 tons from the old furnace. The series of catwalks allowed workers to inspect furnace plates and effect repairs during overhauls.

Both new furnaces incorporated advanced designs by the company's Vice President James Pickering Dovel, including new methods of reinforcement, a system to clean and conserve the gases produced by the smelt and new cooling techniques.

Cooling water was piped from the water tower, another signature feature of the Sloss Furnaces skyline.

After circulating around the furnace, it was piped to a pond (below) and sprayed into the air to cool. After settling in the pond, it was pumped back to the water tower.

80 million cu ft of gases were produced per day by the furnaces. Piped to domed Dust Catchers, solid particles settled into funnels at the catcher's base and were periodically dumped into rail cars and removed.

The cleansed gases were then burned in the Blast Stoves.

Hot air from the Blast Stoves was pumped into the furnace from tuyéres running down vertically from the bustle pipe encircling the bosh, just below the lower catwalk in the photo on the left.

The tuyéres were cooled as part of the furnace's complex water cooling system.

Above, Casting Shed No.1, 128' long and 50' wide. Originally oriented north-south, it was enlarged and rebuilt on an east-west axis in the 1920s to provide more casting space.

The furnaces were tapped by hand in a process called a "melt". Workers periodically opened plugs at the base using sledgehammers, hand drills and crowbars to release the white hot iron. The 150° F heat was so intense that men could only spend 2-3 minutes at this before being replaced by another worker. Immediately on being released, the iron ran into a trench called a runner on a sand bed sloping down to the far end of the shed. Smaller channels, called "sows", ran off at right angles towards the walls leading, in turn, to hundreds of individual pigs.

The sows were opened and closed by cast iron plugs using hand held tools. Once the pigs were filled, the furnace had to be plugged using clay balls, rams and stopping hooks. Slowly cooling,

the pigs were covered in sand and then separated from the sows by workers wielding sledgehammers. They were then carried across the loose sand to waiting rail cars. Each bar weighed 100 to 125 lbs.

Above, a view inside Casting Shed No.1 showing what remains of the casting sand bed.

As ore, limestone, coke and hot air were fed into the furnace, molten iron and slag continuously accumulated in the bottom or hearth. With new Furnace No.1, both were drawn through holes called notches, which were opened every four hours or so.

Molten iron then flowed through a curved trough, called a runner, to a waiting Ladle Car, which would feed the newly built pig caster.

Although the casting shed remained, pigs were no longer produced there.

Above, the furnace iron notch and runner leading to the Ladle Cars.

The slag notch, shown in the upper right, discharged through a trough into pits beside the Cast Shed or, from the late 1940s, into the granulator shown on the lower right. Much more slag was produced than iron, so workers had to "flush" it from the furnace more often. In the slag pits, it was sprayed with water to cool, loaded by shovel crane onto railroad cars and carried to the company's slag plant.

In the granulator, above, slag was sprayed with water to cool it quickly and give it better cementing properties. It was then crushed by drum shaped granulators.

Granulated slag was used in cement. Regular slag was used to make concrete and paving.

When the car arrived at the Pig Caster, it tilted forward, discharging the iron through a spout into a continuous chain of bucket shaped moulds. These were coated with a mixture of coal dust and powdered limestone to prevent sticking and were sprayed with water as they travelled forward. The cooled 45-50 lb pigs were tipped into a waiting rail car at the end of the chain.

The Pig Caster was sold to the American Cast Iron Pipe Company in 1975, and little remains of it other than the frame that supported the chain where pigs were released into rail cars (below).

Above, the runner emerging from the casting shed to one of the Ladle Cars.

Built by W. & P. Pollock of Youngstown, OH, the one hundred and twenty-five ton cars were lined with heat resistant bricks to keep the iron hot. Known as "Bull Ladles" because of their size, paddles stirred the molten iron to homogenise it as they travelled along rails to the new Pig Caster. With the greater capacity of the new furnaces, the cars were probably introduced because it was no longer possible to clear the sand beds of pigs before the next melt.

What is apparent from the many information signs on the site is the large proportion of African Americans that worked at the furnaces.

The black population of Birmingham had multiplied from 5,000 in 1880 to 30,000 in 1890 and formed 39% of the entire population by 1900, the highest percentage of any city in the US at the time. It was a vital component in a regional labour market that used low wages to compete with the North. At the furnaces, only whites worked in supervisory roles, as managers, engineers or accountants. African Americans overwhelmingly worked at labour intensive jobs, while a small mixed race group performed skilled or semi-skilled work.

Sloss-Sheffield was slow to modernise because there was no need while this large labour pool was available and willing to work at dangerous jobs filling and tapping furnaces, casting molten iron and loading heavy pigs onto rail cars.

However, there were other reasons for the reliance on labour intensive work practices.

The presence of phosphorous and silica in Alabama iron ore and sulphur in Warrior coal made iron produced in the state difficult to convert into steel. For those reasons, along with the fact that it was already making excellent profits from pig iron, Sloss-Sheffield chose in 1902 to abandon efforts to make steel and stick with pig iron.

From 1887, when it took outright control of the Coalburg Coke and Coal Company, the Sloss companies also used overwhelmingly African American convict labour in its coal mines, which it leased from the state: by the mid 1890s, convicts comprised 36% of the company's entire mining work force. This was literally a captive work force, not able to take time off or leave the work place. It was also a potent weapon against strikes, permitting continuing operations during walkouts.

At Coalburg, conditions were bad. Convicts were housed in a two storey wood-plank barracks between a fetid stream and a bank of coke ovens. They spent nearly 12 hours a day, six days a week, working in the mines. Medical care was minimal and many convicts worked with serious illnesses, open wounds and infected sores. An annual death rate ranging from 9% to as high as 30% was accounted for by disease hastened by malnutrition, rock falls, crushing by machinery and suicides.

In 1902, the company moved 1,200 convicts to its new Flat Top mine. Whippings, beatings and confinement to tiny "dog houses" continued there until 1928 when the convict system was finally repealed by the state after a prolonged public outcry over the 1924 punishment and death of a white convict at Flat Top.

During the 1930s, Sloss-Sheffield also used violence to suppress unionisation and, in the 1940s, the Union Steelworkers of America further reinforced white supremacy by race baiting and intimidation of black workers seeking to unionise.

The company housed its African American workers near the furnaces in an area known as Sloss Quarters, bounded by 32nd and 35th Streets and 1st and 3rd Avenues.

These shotgun houses, so called because you could fire a shotgun unimpeded from the front porch out the back door, sat next to one of the company's slag dumps. There were gaping holes in the walls, and badly built privies in back yards were shared by as many as ten families. Most bought groceries from the Sloss commissary using company coins known as "clacker" or "dougaloo", and the houses were only demolished in the 1950s to make way for new company headquarters.

During much of the first half of the 20th Century, dust and soot from furnaces, foundries and rolling mills blanketed Birmingham and contributed to one of the highest rates of tuberculosis and pulmonary disease in the US, but blacks living in the city were five times more likely to die of tuberculosis than their white neighbours. Wealthy citizens, by contrast, moved to higher ground, ironically to the crest of Red Mountain, which was one of the sources of the very soot and smoke they sought to escape.

Related Links:

Sloss Furnaces Website

SLSF Historical and Modeling Society

Birmingham Rails Website

Send a comment or query, or request permission to re-use an image.

W. David Lewis' Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District published by the University of Alabama Press in 1994 gives a detailed history of the furnaces. For historic pictures, see Karen Utz's Sloss Furnaces: Images of America published by Arcadia Press in 2009.

Douglas A. Blackmon's Slavery by Another Name provides a ghastly history of the convict leasing system in the South from the 1860s to the 1940s (click on the cover to search for any of these books on Bookfinder.com).