The Roundhouse Railroad Museum in Savannah, GA, is part of the Coastal Heritage Society of Georgia and is open 9.00am-5.00pm daily. It has quite a small collection

of equipment, but this is amply compensated by its

setting and the range of historical buildings it encompasses. It is part of a 32¼ acre site that includes the headquarters, passenger depot, freight depot, workshops and old right of way of the Central Rail Road and Canal Company, from 1895 part of the Central of Georgia Railway.

Work started on buildings in 1836. By 1850, however, the railroad had outgrown the first shops and the then Superintendent, William M. Wadely, conceived an integrated railroad complex, with passenger and freight depots, and shops for the construction and repair of locomotives and rolling stock. Completed in 1855, a number of the original buildings are now part of the museum complex and others have survived in various uses nearby.

There is a pedestrian entrance to the museum on

W Harris St (above centre). If you drive to the museum, you turn into the car park from Louisville Rd.

The Ticket Office is on the ground floor of the old Foreman's Office, built in 1926 when the roundhouse was rebuilt. The Foreman issued orders to shop crews and mechanics from this office, as well as scheduling locomotives and maintenance work on the lines.

The top floor held the engineers' lockers, toilets, showers and washing facilities.

The original roundhouse was built in 1855 and, at that time, formed a complete circle. However, half of the building was demolished in 1926 and most of what remained was reconstructed to accommodate the larger locomotives then coming into use on the Central.

The rebuilt roundhouse included seven stalls forming a back shop area (on the far left above). Each stall had 3'-4' pits to allow access to the running gear of locomotives and rolling stock. On the right is the overnight shed, used for storing locomotives overnight. It also has pits to allow work to engines. The museum still uses the overnight shed for its preservation work.

The current turntable was moved here from Central of Georgia's Columbus, GA, shops in 1923. It was extended 5' in 1945 to make it 85' long, and is still operational and used by the museum.

Above, a view of the overnight shed from the rear. The low building on the left is the "Colored Shopmen's Locker and Lavatory".

Prior to the Civil Rights era in the 1960s, African-American employees on the Central of Georgia faced discrimination and segregation. They typically filled labouring or semi-skilled jobs, with little prospect of advancement. For example, while there were many black hostlers and firemen on the railroad, management's views that blacks were only suited to manual work combined with their exclusion from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen meant few were promoted to engineers. As part of the South's "Jim Crow" laws, there were also separate toilets, washrooms and drinking fountains. Just like dining facilities, rest rooms and drinking fountains in southern railroad passenger depots, these were signposted "White" and "Colored".

While racial inequality on the railroad was sanctioned by state law in the South, it could also be severe in the North. A number of railroads there enforced segregation of African-Americans in the work place, and few among them held skilled positions. Instead, they were overwhelmingly limited to the relatively lowly, and often more dangerous, roles of brakemen, roundhouse and blacksmith helpers, scrap yard workers and track gangs.

Below, two more views of the "Colored Shopmen's Locker and Lavatory". These were part of the original 1855 roundhouse building. The white washrooms were near the Workers' Garden, less exposed to the soot and dirt of the roundhouse.

Railroads in the North and South had incentives to hire African-American workers: they earned 10-20% less than whites, although managers often argued this reflected differences in productivity. A form of racial paternalism also meant white engineers often preferred African-American firemen, who might be expected to serve as their messengers and valets.

Above, two views of the Workers' Garden. The white washrooms are located in the single storey building at the front.

Workers' gardens were not an uncommon sight in US railroad shops, and there was often friendly rivalry between yards over prize flowers and vegetables. Employers saw them as offering workers respite from the din of the shop's engines, hammers and tools, and they were part of the social life of the shops, which included branches of local labour associations, sporting clubs and workers' picnics.

The garden's creation is credited to a rose enthusiast and Master Mechanic named Whitehurst. The fact that his two room ground floor office (on the left in the photo

on the right) overlooked the garden may

have had something to do with his enthusiasm for it.

The garden was removed by the Southern Railway in 1963 but restored by the Coastal Heritage Society's Preservation Team in

2004-05. The design is based on one from about 1900.

Above, the Tender Frame Shop and Master Mechanic's Office. The right hand side of the ground floor housed the Tender Frame Shop, where wooden frames for locomotive tenders were built. A single storey Tender Frame Shop was completed in 1855. In 1899, a second storey was built for blueprinting, drafting and one of the first chemical laboratories in the US.

Eventually, wooden tender frames were replaced with metal frames, which made the Tender Frame Shop obsolete. It later housed scientific and air brake testing laboratories.

Below, all that remains of the old Machine Shop are ghostly machine foot stones and the original perimeter walls.

A single storey Machine Shop was completed in 1855. It housed large machines for finishing iron work produced in the Blacksmith Shop, for milling pipes and bolts, and re-tiring train wheels. The machines were powered by belts driven from the site's Boiler Room. A second floor was added in 1876, but the roof and remains of the building were destroyed by Hurricane David in 1979.

Completed in 1855, the Blacksmith Shop (above and right) housed thirteen forges to produce a variety of items, from locomotive and rolling stock parts, to hinges and door handles for buildings, tools and equipment for the shop workers.

The forges were powered by belts running off a shaft connecting the shop to the Boiler Room next door. Each forge had an underground flue to discharge coal smoke, and these were connected to a central flue that exhausted through the shops' main smokestack.

Following closure of the shops in 1963, the original equipment was removed and, like much of the rest of the complex, the Blacksmith Shop fell into disrepair.

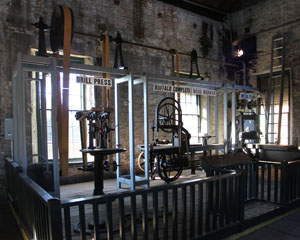

Today, the Blacksmith Shop displays various historic belt-driven and other machinery of the type that would have been prevalent throughout the shop complex.

On the left, the remains of one of the underground flues clogged with dirt.

The Boiler Room was completed in 1855. The front housed a steam boiler in one room and a single column beam engine in another. A two storey room at the rear provided storage for machinery patterns. Some time in the 19th century, the ventilation monitor was added to the roof.

At one time, the Boiler Room provided heat and power for the entire shop complex through a series of line shafts and belt drives. In 1907, electricity replaced steam to power machinery, but the Boiler Room continued to supply heat to the complex.

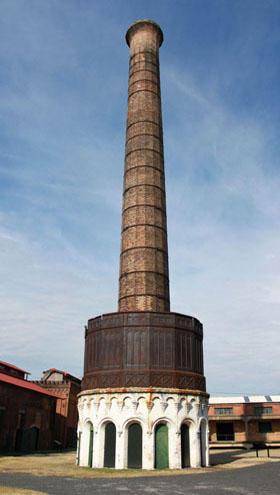

Above and above right, the 125' tall smokestack dominates the shop complex and is visible for some distance as you approach the site. It was completed in 1855 and exhausted smoke and steam from the Boiler House and Blacksmith Shop via underground brick tunnels.

The wrought iron straps were added in 1902 when the masonry underwent major repairs to fix damage probably caused by lightening strikes.

Above, looking down the stack from inside the ground floor part of the structure.

Built of Savannah Grey brick and lime mortar, its height and the wind blowing across its opening at the top drew smoke through the tunnels and up the stack.

The Carpenters Shop, completed in 1853, was originally part of a larger u-shaped building. It suffered a major fire in 1923 and was then rebuilt as a smaller, stand alone shop. Another fire in 1987 destroyed much of the internal parts of that building and all that remains now is a shell (below top).

Since 2003, the Coastal Heritage Society of Georgia has been working to stabilise and protect what is left of the Carpenters Shop. It has been designated a "Save America's Treasures Official Project" and, when the reconstruction is complete, the building will become part of the museum. Below bottom, the Carpenters Shop and, on the right of the photo, the Boiler House from W Jones Street.

The Lumber Shed (on the left above) was completed in 1855. The ventilation monitor on the roof was added some time later in the 19th Century. In 1907, the shed was converted to house compressors, generators, transformers and a dynamo to feed electricity to the shop complex. Electricity was supplied by a local utility company.

While it operated, wood from the Lumber Shed was easily to hand for

the Planing Shed (on the right above). There, workers milled lumber for tender frames until these were superseded by metal construction, for passenger carriages, freight cars, rolling stock and any other wooden items used by the railroad. Below, behind the Planing Shed and Storehouse, the final fabrication of wooden items was completed in the Carpenters Shop.

Above and left, built in 1925, the Storehouse held parts for rolling stock and locomotives, as well as other supplies required for the railroad's operation.

It housed the Print Shop where all the complex's printing needs were met, from inventory forms to the house magazine.

Left, the Print Shop has been preserved much as it would have appeared in 1926.

On display are a linotype machine, offset printing presses, a letter press, perforator, paper cutter and embossing machine, as well as a variety of small tools and printing blocks.

The 74' x 211' single storey Coach Shop was built in 1925. It was used to carry out major

repairs to Central's rolling stock.

Cars would enter

through three doors (on the right in the view above) from a transfer table on the north side of the building.

Below, a view of the 227' x 211' Paint Shop from the corner of W Jones and W Boundary St. This building was used for stripping and painting all types of cars, wood, steel, passenger and freight.

The floor of the upper level is made of reinforced concrete and is supported by large concrete columns in the lower level. Here, there were storage areas for materials, offices, a stationery and multigraphing department, an electrical department and an area for producing upholstery, tin items and cabinets. Employees also tested paints here, lubricants, oils, adhesives and other materials used by the Central.

The Coach Shop (above left) and Paint Shop (above right) were both built on the footprint of two 1907 buildings that were destroyed by fire in 1923. The new buildings featured fire-proof building materials, automatic fire doors and sprinklers throughout.

In the view above, the original transfer table that fed cars to both shops once occupied a large part of the area where the trees are now growing. Below, a view from W Boundary St of the old stone footings that supported the western end of the transfer table.

Below, the bridge that fed trains from the work shops, the depot and freight warehouses to Central's main line was built in 1852 to cross West Boundary St and the Savannah and Ogeechee Canal. One hundred and fifty feet long, it is constructed of Savannah grey brick.

In use for one hundred and sixty-nine years, the bridge carried trains of large steel passenger cars, as well as heavy diesels during its final years, without ever having been reinforced. The Nancy Hawks II was last train to cross the bridge on 30th April 1971, headed for Atlanta, GA.

The Coach Shop and Paint Shop were acquired by the Coastal Heritage Society from Norfolk Southern, the successor to Southern Railway, in 2003. Up until then, they had been prey to squatting and vandalism, as is evident in the photos above of the lower level of the Paint Shop taken by my brother.

In 2005, the CHS started a comprehensive programme of remediation and repairs. Once this is completed, the Coach Shop and lower level of the Paint Shop will house the Savannah Children's Museum. The upper level of the Paint Shop will be used to exhibit historic rolling stock.

Above, this neo classical style building on the corner of Martin Luther King and Turner Blvds was constructed between 1854 and 1856 as headquarters for the Central. A depot behind the office served both freight and passengers until Central's new depot opened in 1876. Thereafter, it was used as the Up Freight Warehouse.

The building served as a railroad office for one hundred and thirty-six years, the longest use for this purpose in the US. Norfolk Southern vacated the building in 1991, and it is now the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum.

The Romanesque style building above was designed by Alfred Eichberg and Calvin Fay. Built in 1887 as offices for the Central, it is now known as Eichberg Hall and houses the architecture, interior design and urban design departments of the Savannah College of Art.

The building behind Eichberg Hall (right) was designed by William Wadley. Built in 1853 as part of the railroad complex, it was the Down Freight Warehouse for the Central. Vacant by the middle of the 20th century and facing demolition, it was acquired by the Savannah College of Art in 1988.

The old entrance gate to the Central of Georgia's railroad shops and offices is just south of the

office building on MLK Blvd.

Passenger platforms and freight loading once occupied what is now the parking area inside the gates.

The Roundhouse Museum complex is part of a larger historic district that includes the old Central of Georgia Savannah Depot (above) and train shed (right), which were both part of William M. Wadely's original railroad complex. Costing more than $500,000, this was a forerunner of the type of comprehensive facilities planning that was to become standard railroad practice in the last quarter of the 19th Century.

The Romanesque Revival depot on Martin Luther King Blvd and the train shed on Louisville Rd were both designed by Augustus Schwaab, a German immigrant then working as an engineer for the Central. The last major features of the railroad complex, they were started in 1861, and the train shed is the oldest surviving example of early iron roof construction, the first step in the evolution of modern steel frame building. However, work on the depot was interrupted by the Civil War and it was not opened until 1876.

The depot was closed in 1971. Along with the train shed, it was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976 and, since 1990, has housed the Savannah Visitors Center and the Coastal Heritage Society museum.

Baldwin built Ten Wheeler (4-6-0) type Central of Georgia #403 is on display inside the Coastal Heritage Society museum.

It lacks its tender, which is apparently stored at the Roundhouse Museum.

Built in 1905 for the Stillmore Air Line as

#103 (later merged into the Wadley Southern), the locomotive was sold to the Sylvania Central in 1920. In 1954 when then owner, Central of Georgia, abandoned the railway it was renumbered #403 and leased to the Talbotton Railroad where it operated until 1957.

A coal burner, #403 weighs 97,000 lbs, and has 56" drivers and 16" x 24" cylinders. Operating at a boiler pressure of 180 psi, it delivered 16,780 lbs tractive effort.

0-6-0T #8 is the oldest Central of Georgia locomotive in existence. It was built by Baldwin in 1886 as a conventional steam locomotive (i.e. with tender) but was converted to a saddle tank by the CG shops in Macon, GA, in 1909.

It served as a switch engine in the Macon area until 1953, and was christened "Maude" after the stubborn, back kicking comic strip mule in Frederick Opper's "And Her Name Was Maud".

#8 weighs 100,000 lbs, has 18" x 24" cylinders and 51" drivers. It operated a boiler pressure of 145 psi delivering tractive effort of 19,168 lbs.

This locomotive was outshopped as demonstrator model #905 by EMD on 4th August 1939 but was almost immediately sold to the Central of Georgia. Delivered to the Savannah shops on 13th August 1939, it was the

first diesel-electric bought by the railroad. It switched freight and passenger cars at the shops as well as on Central's nearby Seatrain Terminal on the Savannah River.

The Central took delivery of another three SW1s: #2 and #3 in January 1941, and #7 in December 1941. #1 was sold to Atlanta Stone Mountain & Lithonia Railway in January 1957.

Above, on one of my visits to the museum the access panels were open on #1.

Six hundred and sixty-one of these 600 hp switchers were built by EMD from 1938 to 1953, all but one for US railroads. Pre-1945 units were powered by an EMD 567 prime mover. Post-1945 models had an improved 567A prime mover. They weigh 201,500 lbs and deliver 34,000 lbs tractive effort at 11 mph. You can see other SW1s on the B&O Museum Yard & Car Shop and Illinois Railway Museum Yard pages of this website.

#2715 is the last of eleven GP35 diesel-electrics delivered to the Savannah

& Atlanta Railroad by EMD between 1964 and 1965.

One thousand, three hundred and thirty-three GP35s were built from 1963 to 1966. With

a 2,500 hp 567D3A 16

cylinder prime mover, they delivered 50,000 lbs tractive effort at 9.3 mph.

The Savannah & Atlanta Railroad was incorporated in 1915 to connect the

Georgia Railroad at Camak, GA, and the Savannah & Northwestern

Railroad at St Clair, GA. Two years later, it absorbed the Savannah & Northwestern.

The Savannah & Atlanta went bust in 1921 and was bought by Robert M. Nelson. Central of Georgia purchased the line in 1951 for $3,500,000, although it retained

its corporate identity until 1982 when it was absorbed into newly created Norfolk Southern Railway.

Since 2007, #30 has steamed on occasion at the museum, but it has been undergoing repairs each time I have visited.

This 0-4-0T (Tank) locomotive was built by Alco for Hardaway Contracting Co. in 1913 as #105, and then passed through several owners before being bought by Georgia Power as #30. It last operated at the company's Arkwright Plant switching coal cars.

#30 weighs 61,000 lbs, and has 34" drivers and 13" x 18" cylinders. It can deliver tractive effort of 12,400 lbs.

This 0-4-0T (Tank) engine was built in 1905 by H. K. Porter of Pittsburgh, PA, for Wellerman-Seaver- Morgan Engineering of Cleveland, OH.

It was later sold to the scrap dealer Southern Iron & Equipment Co. of Atlanta, GA, and then to Atlantic Steel.

#1 worked at Atlanta Steel until the end of WWII, by which time its small size had rendered it obsolete. It weighs 24,500 lbs, has 27" drivers and

9" x 14" cylinders. A coal burner operating at a boiler pressure of 140 psi, it delivered 4,995 lbs tractive effort. It still has its original couplers, in which a pin was dropped by hand into a link to couple cars.

H. K. Porter began production in 1866 as Smith & Porter and became the largest US producer of small industrial locomotives, building almost eight thousand of them, mainly steam locomotives but also some fireless, diesel, gasoline and compressed air powered models. There are three hundred and fifteen Porter locomotives preserved worldwide. Although it stopped producing locomotives in 1950, the company continues to produce industrial equipment to this day.

When I visited in 2004, Scott Lumber #15 was standing in the roundhouse but, on my other visits, it has been off site undergoing restoration.

#15 was built for the Scott Lumber Co., of Marlboro, SC, by Baldwin in 1914. It was later sold to a subsidiary company, Holly Hill Lumber Co., of Holly Hill, SC. In 1962, it was then bought by Western Heritage USA of Silver Spring, FL, and passed through several owners before being purchased by the Patsiliga Museum of Junction City, GA. It is on loan to the Roundhouse Museum.

#15 is a Columbian type (2-4-2)

locomotive weighing 52,000 lbs, 34,000 lbs on its 42" drivers. The engine wheelbase is 19' 4" and driver wheelbase 9'. A coal burner with 12" x 18" cylinders, a 10.2 sq ft grate and 46 sq ft firebox, total heating surface was 509 sq ft. Operating at a boiler pressure of 160 psi it delivered 8,400 lbs tractive effort. The tender weighs 41,000 lbs light with a 3 ton coal and 1,800 gallon water capacity.

This diesel-electric switcher was built by General Electric for the US Army in 1942. It is powered by two Caterpillar D 1700 diesel engines delivering 300 hp.

#7069 worked at the Army's Deseret Chemical Warfare Depot in Clover, UT, and was later transferred to the US Air Force. The Claremont Concord Railroad in New Hampshire bought #7069 in 1988 and it worked for the railroad until 2008, when it was purchased by the Coastal Heritage Society to join the museum's collection.

This 380 hp diesel-electric switcher was bought from General Electric by the Boston & Maine in 1948 as #119. It was the last of ten GE 44-Ton switchers bought by the railroad between 1940 and 1948.

#119 was later purchased by Pinsley Railroad, a shortline holding company, and then moved to the Claremont Concord Railroad. It was in service until 2004, when it was sold to the museum. Some time before its sale, #119 was repainted in its original delivery colour scheme and was named "William P. Dow".

Georgia State Railroad Museum's 10 ton Davenport DM10 industrial switching diesel locomotive #10 was originally owned by the North Florida Railway as #2.

The Davenport Locomotive Works, of Davenport, IA, produced locomotives from 1902. The company started out building small steam locomotives but went on to produce the first gasoline-fuelled locomotive in 1924 and the first diesel

locomotive in 1927. It then produced an extensive range of diesel locomotives in all industrial types and sizes until the works closed in 1956.

This narrow gauge (3') 0-4-0F (Fireless) locomotive was built by H. K. Porter in 1921 to operate in a sugar beet factory. It was apparently ordered as a cab-forward, but was later converted to a standard configuration.

#9 is typical of light weight locomotives used in agriculture where temporary rails were often laid so that cars could be loaded close to a harvest and then transported to the factory. It weighs 10,000 lbs, has 5" x 10" cylinders and 21" drivers, and could deliver 1,700 lbs tractive effort.

When I visited in 2004, #223 was stored in the roundhouse awaiting restoration.

It is now on display beside the turntable and looks much better for the work done on it.

The locomotive was built by Baldwin and delivered to the Central of Georgia as C-3 Class #1223, one of a batch of twenty-five Consolidations (2-8-0) built for the railroad in 1906. At some point, it was renumbered #223 and sold to the Wrightsville & Tennessee, before being retired in 1952.

Designed for fast freight service, #223 has 57" drivers and 20" x 28" cylinders. It weighs 167,000 lbs and operated at a boiler pressure of 200 psi delivering tractive effort of 34,000 lbs.

This all purpose, light weight Burro Model 15 Crane and integrated crane car was built by the Cullen-Friestedt Company of Chicago, IL for the New Hope Valley Railway. The "Burro" cranes were named after the favoured pack animal of the old West, a Spanish breed of donkey.

#1005 was used for maintenance of way work, such as lifting rails and ties, installing signalling equipment or point systems. The boom can be fitted with different tools depending on the assignment, from the simple hook shown here to an electromagnet.

This little engine is housed in the museum's Tender Frame Shed. Built in Charleston, SC, some time between 1858 and 1860 by Smith & Porter, it is the oldest known wheeled portable steam engine made in the US.

A fore runner of the steam traction engine, these were ideal portable power sources for use in agricultural, construction and industrial settings.

This engine worked cutting firewood for other steam engines at Cedar Key, FL, but was abandoned when a hurricane closed the business in 1878.

Related Links:

Savannah Roundhouse Railroad Museum Website

Georgia Railroads Page on the Roundhouse Museum

Savannah Shops Application for World Heritage Listing

Central of Georgia Railway Historical Society

Send a comment or query, or request permission to re-use an image.

Right, Central of Georgia Railway by Jackson McQuigg, Tammy Galloway and Scott McIntosh was published by Arcadia Press in 2004 (click on the cover to search for this book on Bookfinder.com).

Left, Theodore Kornweibel's Railroads in the African American Experience, was published by the Johns Hopkins University Press in 2010 (click on the cover to search for this book on Bookfinder.com).