The Museum of Science and Industry is in Jackson Park in the Hyde Park neighbourhood of Chicago, IL. It is the largest science museum in the western hemisphere and is housed in the former Palace of Fine Arts designed by Charles B. Atwood for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. The science museum was initially endowed by Sears, Roebuck and Company president and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, and opened in 1933 during the Century of Progress Exposition.

The museum has over two thousand exhibits in seventy-five major halls, including a recreation of a working deep shaft bituminous coal mine, the U-505 Submarine, one of just two German submarines captured during World War II, and the only captured one now on display in the Western Hemisphere, the Apollo 8 spacecraft which flew the first humans to the Moon and Chicago, Burlington & Quincy #9900, the first diesel-powered streamlined stainless-steel passenger train in the US.

Like most museums of this kind, the MS&I gets very busy very quickly. So get there early if you want some good shots of the equipment on display.

Above, a view of the museum's impressive original entrance portico. For years visitors entered here, but it proved too small to handle a large number of people and a new main entrance was installed detached from the main museum building. From there, visitors descend into the main entrance area and then re-ascend to the various exhibition rooms.

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Pioneer Zephyr #9900 is on display in the Great Hall and there is a free tour of the trainset every 10-20 minutes.

#9900 was built in 1934 with bodywork and passenger cars by the Budd Company and engine, transmission, power truck and other equipment by EMC.

It was the first of the CB&Q's fleet of Zephyrs, one of the largest and most famous fleets of streamliners in the US.

With the US then in the depths of the Great Depression, and both freight and passenger railroad revenues down, the fleet was conceived as a means of encouraging passengers back onto the rails.

Originally christened the Zephyr, #9900 was built entirely of welded stainless steel. Aeronautical engineer Albert Gardner Dean designed the sloping nose, with architect John Harbeson and industrial designer Paul Philippe Cret devising a way to strengthen and beautify the sides of the train with its distinctive horizontal fluting.

Above, the engineer occupied a cramped space right in front of the prime mover in the power car. It must have been hot, noisy and uncomfortable up there.

Below, the baggage

coach car #505 could carry 50,000 pounds of baggage and had a 30' long mail compartment.

Above, an 8-cylinder,

600 hp, 8-201-A model Winton engine powered #9900.

#505 also had a short buffet and twenty passenger seats. The third car #570 was half coach, with forty passenger seats, and half observation car with twelve passenger seats.

The three cars rode on four roller-bearing trucks, forming a permanently articulated 197' long trainset weighing 193,000 lbs.

The Zephyr's christening was on 18th April 1934, at the Pennsylvania Railroad's Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, PA.

On 26th May 1934, the train set out on a one thousand and fifteen mile non-stop "Dawn-to-Dusk" dash from Denver, CO, to Chicago, IL.

The train left Denver at 7.04 am Central Daylight Time and arrived in Chicago at 8.09 pm, thirteen hours five minutes later, one hour fifty-five minutes faster than scheduled. It averaged 77 mph and, for one section, reached 112.5 mph, close to the then world land speed record of 113.6 mph. Reporters along the route referred to it as the "Silver Streak", running faster than any other train on American rails at the time.

From Chicago Union Station, the trainset went on display at the 1934 Century of Progress fair. After the fair, it started a thirty-one state, two hundred and twenty-two city publicity tour, during which more than two million people saw it.

The Zephyr entered revenue service on 11th November 1934 between Kansas City, MO, Omaha and Lincoln, NE. By June 1935, it had proved so popular that a fourth coach car, #525, was added to the trainset seating forty.

It set new standards in passenger service and formed the model for other railroad's streamlined trains as well as the CB&Q's later Zephyrs.

The original Zephyr was renamed the Pioneer Zephyr in 1936 to distinguish it as the first of CBQ's growing Zephyr fleet.

The CB&Q eventually rostered nine ZephyrsThe last, #9908, is in the National Museum of Transportation, St. Louis.

By 1955 the Pioneer Zephyr's route had been updated to run between Galesburg, IL, and Saint Joseph, MO.

Its last revenue run was on 20th March 1960 from Lincoln, NE, to Galesburg, IL. On 26th May 1960, it was presented to the museum, having run 3,222,898 miles in service.

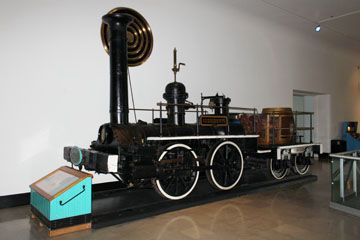

The New York Central & Hudson River Railroad's long running rivalry with the Pennsylvania Railroad over the New York-Chicago passenger service came to a head with the announcement of the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. To steal a march on the Pennsy, the NYC unveiled this 4-4-0 American type locomotive, #999. Designed by NYC&HR's chief Superintendent of Motive Power & Rolling Stock, William Buchanan, it was built at the railroad's West Albany, NY, shops in the spring of 1893 at a cost of $13,000.

It must have been a sight when it was unveiled: the boiler, smokestack and cylinders finished in blue-grey Russia iron, the brass details, exposed pipes and edges polished, aluminium striping outlining each stave of the wooden cowcatcher, driver spokes and counter balances, the railroad's initials emblazoned on the tender's slope sheets, on the flanks of which in bold, aluminium leaf script was the name of the train it would haul, the Empire State Express.

#999 entered service on 9th May 1893, hauling the Empire Express from Syracuse, NY, to Chicago, IL, with Engineer Charles Hogan and Fireman Al Elliott at the controls.

As the train neared East Buffalo, NY, Hogan gave #999 its head. Slowly the speed rose until, at about milepost 423 just before the curve leading to Rochester, it was recorded by several people on board momentarily reaching 112.5 mph, theoretically making it the fastest moving man-made object of its time and the first on wheels to exceed 100 mph.

#999 went on display for the duration of the Colombian Exposition described as the "Fastest Locomotive in the World". It then entered regular service on the Empire State Express, working the more level segment between Syracuse and Buffalo, NY.

Although tried on other parts of the system, #999 was found to be too slippery and hard to handle on trains exceeding five passenger cars.

Above, #999's backhead. A coal burner, the engine weighs 124,000 lbs. With a 30.7 sq ft grate, 232.92 sq ft firebox and total heating surface of 1,930 sq ft, it operated at a boiler pressure of 180 psi delivering 18,940 lbs tractive effort. When built, #999 was fitted with 86½" drivers (the front truck and tender wheels were 40"), but these were later reduced to 78" and then 70" when the locomotive was shopped.

By the 1920s #999 had been moved to the general passenger motive power pool along with all the other NYC 4-4-0s. In 1938, #999 appeared at the New York World's Fair and, in 1948-49, at the Chicago Railroad Fair. Shortly after, however, the NYC turned its back on steam motive power and the locomotive went into storage.

Rendered obsolete by techological advances in locomotive design and the eclipse of steam by diesel-electrics, in May 1952, following a

re-enactment of its record breaking run, #999 was officially retired from service.

The New York Central donated #999 to the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry in 1962, although it did not arrive until 1968 when it went on display outdoors. Following a complete restoration from June to October 1993, the locomotive was then brought inside to its present location in November 1993.

This is a replica of an 0-4-0 steam carriage built by the lawyer, engineer and inventor John Stevens. The first railroad charter in the US was granted to Stevens and others in 1815 for the New Jersey Railroad.

Stevens built the original steam carriage in 1825 and operated it on his Hoboken, NJ, estate hauling several passenger cars at a time at a speed of 12 mph.

The replica was built at PRR's Altoona shops and donated to the museum in 1932. In 2015, it was sold from the collection. It weighs 4,575 lbs, has 57" drivers and a single 5" x 12" cylinder. Operating at 100 psi, it delivered 530 lbs tractive effort.

You can see another replica "John Stevens" on the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania Train Shed page of this website.

The original 0-2-2 "Rocket" won Stephenson £500 at the Rainhill trials, a competition set up by the Liverpool & Manchester Railway to determine the best motive power to employ on the railroad. Ten locomotives were entered, but only five competed. The "Rocket" was the only one to complete the three day trials, starting on 6th October 1829, over which it averaged 12 mph and achieved a top speed of 30 mph.

Stephenson was consequently awarded the contract to build locomotives for the Liverpool & Manchester.

This replica of the "Rocket" was built in 1931 by Robert Stephenson & Co., in Darlington, England (the original was built by the company in 1829).

The Stephenson Company was established in 1823 to build steam locomotives and survived through various owners, acquisitions and mergers until the last conventional steam locomotive, an 0-6-0T, was built in 1958 and a six-coupled fireless locomotive in 1959. The Darlington Works continued building diesel and electric locomotives and became the English Electric Company Darlington Works in 1962.

A coke burner, the original "Rocket" is now on display in the Science Museum in London, England. It has 56½" drivers and weighs 8,500 lbs. Operating at a boiler pressure of 50 psi, it delivered 748 lbs tractive effort. The horizontal boiler and rear firebox, multiple boiler flues and directly connected driving rods pioneered by the "Rocket" became the prototype employed on virtually every subsequent steam locomotive.

You can see the another replica "Rocket" built by the Stephenson Company in 1929 on the Henry Ford Museum page of this website.

The 0-4-0 "York" was the first locomotive to operate on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. This replica was built at B&O's Mt Clare shops in 1927 and steamed at the Fair of the Iron Horse that year and at the Chicago World's Fair in 1933-34.

The original "York", was built in 1831 by Davis & Gartner in York, PA. It was one of three locomotives tested by the B&O in response to a competition to produce a viable US built steam locomotive for the railroad. The "York" weighed 3½ tons and had 30" drive wheels. It was sold in 2015 and is no longer in the museum's collection.

The "Mississippi" transferred to the Mississippi Valley & Ship Island Railroad in 1873. Then, after an accident a few years later, it was salvaged by James Hoskins of Brookhaven, MS, in 1880. Hoskins reconditioned the locomotive and put it to work on his railroad, the Meridian, Brookhaven & Natchez.

In 1891, Hoskins donated the engine to the Illinois Central to be used in their exhibit at Chicago's Columbian Exposition in 1893 and it actually ran under its own power the eight hundred miles to Chicago.

This is the only survivor of the Natchez & Hamburg Railroad, which was built to connect the river port at Natchez with the interior of the state of Mississippi.

A wood burner built in 1836 by H. R. Dunham & Co., in New York, NY, the "Mississippi" operated for only a few years from April 1837 until May 1840 when a violent storm destroyed much of the railroad's property and contributed to its failure. The locomotive went into storage until it was sold to the Grand Gulf & Port Gibson Railroad in 1844.

According to the information panel, this cab is "modelled after" a Pennsylvania Railroad Pacific type (4-6-2) K-4, although the cab was apparently originally on a PRR 2-8-2. It was sold in 2015 and is no longer in the collection.

The Pennsy built four hundred and twenty-five K4

locomotives between 1914

and 1928. They were one of

the most successful

passenger steam locomotives ever built and outnumbered any others of their type on US railroads.

You can see PRR K-4 #3750 on the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania Yard page of this website. There is also a one-sixth scale model of PRR K4 #417 built from 421,250 toothpicks on the National NYC Museum page!

A cut away side of the pilot, front truck, cylinders, valve gear and drivers from what was once a Chicago & Illinois Eastern Atlantic type (4-4-2) locomotive is also on display.

The locomotive appears to have originally been an E-2 class, although the display's date of 1938 is far too late. The E-2 was built in 1905 and had Stephenson valve gear rather than Walschaert.

Visitors can press a button on the side of the railings to see how the wheels, valve gear and cylinders operated.

Related Links:

Museum of Science & Industry Chicago

Burlington Route Historical Society

New York Central System Historical Society

Send a comment or query, or request permission to re-use an image.

Carl R. Byron and R. W. Rediske's Pioneer Zephyr: America's First Diesel-Electric Stainless Steel Streamliner published by Heimburger House Publishing Company in 2005 details the history of the Pioneer Zephyr, including its rebuilding and installation in 1997-1998 in the Museum of Science and Industry (click on the cover to search for this book on Bookfinder.com).