The first part of what became known as the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railroad was completed in 1827. This iron strap wooden rail line was one of the first in the US. It was built by the Lehigh Canal & Navigation Company on a gently descending grade so that laden coal cars would drift under their own weight the 8.7 miles from its Sharp Mountain Quarry in Summit Hill to Mauch Chunk, PA, where coal was transferred to the Lehigh Canal.

Empty cars were hauled back up the track by mules, which then returned to Mauch Chunk in specially built cars attached to the coal trains. Empties had to wait until full cars had completed their down trip before they could return, which created a bottle-neck at Mauch Chunk, and a back track was therefore built in 1845. It consisted of two planes, Mount Pisgah and Mount Jefferson, which used stationary steam engines to haul cars to the top of each plane. Between the planes, cars were once again propelled by gravity on the back track.

The switchback closed in 1933 and most of the rails and buildings were removed in the ensuing years, but you can still walk almost the entire length of the old grade, and much of it is also suitable for mountain biking.

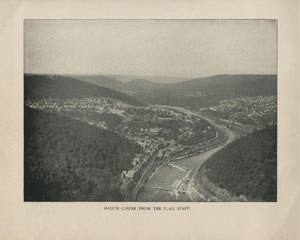

With its mountainous location, forest scenery and mix of picturesque architecture, Mauch Chunk and the surrounding area was soon known as "The Switzerland of America".

Views of the switchback and local attractions featured in portmanteau

works such as Picturesque America, as well as being packaged in souvenir booklets for visitors and tourists, like The Switzerland of America above, published in 1905.

Above, waterfalls in nearby Glen Onoko, from The Switzerland of America.

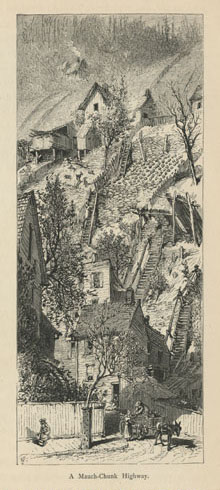

Illustrators were prone to exaggerate the area's perpendicularity, as in Harry Fenn's engraving of "A Mauch Chunk Highway" from the 1872 edition of Picturesque America (vol. I, p. 115).

The town was "so compacted among the hills that its houses impinge upon its one narrow street ... with no space for gardens except what the owners can manage to snatch from the hill-side above their heads" (p. 109).

But "Mauch Chunk from the Flag Staff", right, from The Switzerland of America shows that, although certainly hilly, the area was hardly alpine.

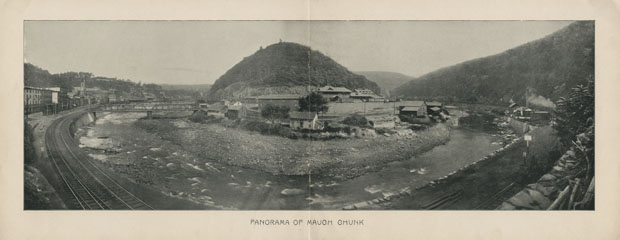

Founded in 1818 at the foot of Mauch Chunk Creek, the town took its name from the Native American Lenape term "bear mountain" after the mountain across the river that was thought to resemble a sleeping bear, at the centre of "Panorama of Mauch Chunk" below, also from The Switzerland of America.

The town owed its existence to the discovery nearby in the late 18th century of anthracite, a hard, compact coal with the highest carbon count and fewest impurities of all coals.

Initially, consumers were unfamiliar with this new type of coal and there were few stoves designed to burn it. However, because of its higher quality and "smokeless" characteristics, it eventually became the most popular fuel for heating homes and other buildings in the northern US until supplanted first by oil burning systems in the 1950s and then by natural gas.

The coal was transported to chutes at Mauch Chunk where it was re-screened. This was necessary because of damage sustained on the ride down the gravity railroad. The arriving coal was also washed at the chutes to recover the fine coal dust.

The processed coal was then shot out into boats waiting on the Lehigh or into cars on the Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad, shown in the engraving below from Picturesque America (vol. I, p. 114).

The coal was processed into different sizes by a breaker, above, from The Switzerland of America.

Toothed rollers reduced the lumps to smaller pieces, which were separated by graduated sieves. In the early 20th

century, six sizes were produced: Steam (primarily used as steamship fuel), Broken, Egg, Stove (mainly used in domestic stoves), Chestnut and Pea, with three sub sizes No.1 Buckwheat, No. 2 Buckwheat and No. 3 Buckwheat.

The proximity of the chutes to the township caused frequent complaints. On 20th June 1843, for example, the Carbon County Transit bemoaned the resulting coal dust "is a blot upon the appearance of the town, giving it (although many miles distant from the coal mines) the look of a colliery" (quoted in Hydro, The Mauch Chunk Switchback, p. 142).

The chutes were finally closed in 1872 when coal began to be transported to Coalport by the Nesquehoning Valley Railroad through the newly built Nesquehoning Tunnel. By the following March, the chutes had been dismantled.

Begun in January 1827, work on the gravity railroad was finished by April, largely because much of the grade was laid over the existing turnpike. The first official trip on 5th May descended with a seven car train bearing White, a group of passengers and several loads of coal. Regular coal runs then started the following Monday.

In early 1845, work began on the back track, which was finished in 1846. The new track halved the time to complete a round trip from four hours to two.

Coal was first transported from the mines down a rough trail hacked out by the Lehigh Coal Mine Company.

In 1818, the land was leased to the newly formed Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, which began to rebuild the trail as a stone turnpike with a view to replacing it with a railroad. In 1826, Josiah White, a partner in the LC&N, built an iron rail test track on what is now the parking lot of the Immaculate Conception Church (above).

The same year the back track was

completed, however, the Pennsylvania Legislature approved a bill to charter the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill & Susquehanna Railroad. Having taken a controlling interest in the railroad in 1851, Mauch Chunk

resident Asa Packer reorganised it into the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1853. Above, Asa Packer's Mansion in Jim Thorpe, now a museum.

Packer had built canal-boats and locks for the LC&N and had urged it to invest in a steam railway but the board declined. Unfortunately for them, the Lehigh Valley Railroad was to become a major competitor.

Through a series of mergers, connections and acquisitions, the LV progressively extended its connections into the upper Lehigh Valley during the 1850s and early 1860s. At the same time, the volume of coal it shipped increased, just as the LC&N faced the consequences of a devastating flood that tore away much of its upper Lehigh canal system.

It responded by abandoning the upper canal, building loading facilities at Coalport across the river from Mauch Chunk and extending its Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad.

The LV completed its line from Mauch Chunk (above, from Souvenir of Mauch Chunk) to Easton in 1855. From there, coal could be shipped to Philadelphia on the Delaware Division Canal or across the Delaware River to Phillipsburg, NJ, where the Morris Canal and the Central of New Jersey could take it to New York.

The railroad also carried passengers to enjoy the local sights. The Mansion House Hotel was just across the Lehigh opposite its East Mauch Chunk station.

By December 1866, the L&SR had connected to the LV below Mauch Chunk and, through an extension from Whitehaven to Penn Haven, directly to Wilkes-Barre. As coal switched to the Nesquehoning Valley Railroad in 1872, the connections paved the way for the town's new life. During the last decades of the 19th Century, it would compete with destinations like Niagara Falls to draw tourists and holiday makers to delight in the sights and thrill to a ride on the switchback railroad.

Above, the L&SR depot at Jim Thorpe. Until this was built in 1889, the ground floor of the Mansion House Hotel functioned as the passenger station.

Above, "Mauch Chunk from the Mountain Road" from The Switzerland of America. The switchback runs across the upper horizon. Packer Hill rises just above the tower on the Mauch Chunk railroad depot (you can see all the views in this booklet on the books and manuals page of this website).

Below, a view across the Lehigh from Souvenir of Mauch Chunk (you can see all the views in this booklet on the books and manuals page of this website).

Passengers could travel to the depot from downtown Mauch Chunk by foot up Packer Hill, by horse drawn coach or, after 1893, by trolley car.

The depot, built in 1872, stood where the trees now grow behind the upright stone in the view above. It was 125' long and housed a ticket office, waiting area and souvenir shop. The original "Switch Back Restaurant" was immediately to the left, where the house now stands. It was pulled down in 1909/10 to make way for the Grandview Hotel.

Above, a postcard dated 1916 shows the original depot at Upper Mauch Chunk in the background on the left. A car loaded with passengers is about to depart from the shed in the foreground on the right.

The switchback usually operated from mid-May to Halloween, with cars leaving the depot about once an hour from 8:30 am to 6:30 pm. Occasionally, there were special "moonlight" trips. Cars were boarded from the depot waiting area or from the shed to the right of the depot, which was used on Sundays and public holidays to meet the heavier passenger traffic on those days.

Above, a view looking north west along the grade a few yards from the location of the depot. In the open area on the right there was a small Repair Shop.

At this point, powered only by gravity, cars would drift slowly down a slight grade to the base of Mt. Pisgah.

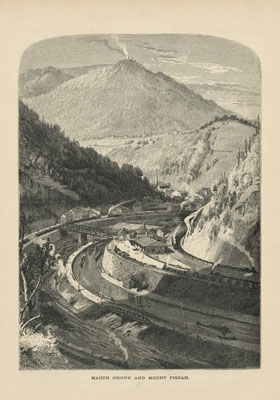

Above, Harry Fenn has crowded this view of "Mauch Chunk and Mount Pisgah" in Picturesque America (vol. I, p. 112) with an unlikely number of trains and engines.

He has also rather exaggerated the height of the hills, as well as Mt. Pisgah, with its engine house smoking dramatically.

Picturesque America reassured its readers of the veracity of the depicted activity along the Lehigh River, claiming: "so continuous [are the trains] coming and going, sweeping now around the foot of the hill opposite, and now around the base of the hill on which we stand, that usually several trains are visible at the same time; and rarely at any moment is the whistle or the puff of the locomotive silent" (vol. I, p. 110).

Above, another somewhat fanciful aerial view by Harry Finn of a car climbing the plane from Picturesque America (vol. I, p. 109).

Above right, an early 20th century postcard showing one of the cars about to start up the Mt. Pisgah plane. The conductor is checking the "barney". These rose from the "barney pit" to the rear of each car and were used to push them up the plane.

Above, looking to the north east across the original location of the Mt. Pisgah "barney pit".

Nothing remains of the pit now and the plane is overgrown with trees.

The photo above was taken from roughly the same position as the view shown in the early 20th Century postcard on the left.

The postcard above, stamped 1908, shows another car about to start its ascent of Mt. Pisgah.

The photo above was taken from roughly the same position as the view in the postcard. The area is now a playing field. In the 1930s, the "barney pit" was filled with earth removed from a cut to allow Route 209 to come into Jim Thorpe from the south.

Above, looking up the plane from the foot.

Above, looking back

from the start of the plane.

You really need to be in good health to climb the entire plane. It is 2,250' long and rises 664' on a 29% grade, although there is an easier walk from North Ave up the "Switchback Trail" to the top of the plane.

Above left, a photo looking down the plane from the top of Mt. Pisgah. On the right, an early 20th century postcard from roughly the same viewpoint.

Having arrived at the base of the plane, the conductor would pull a wire to ring a bell in the engine house and signal that he was ready for the "barney". The engineer would then engage the stationary steam engine, which would wind in long straps of linked iron plates, evident on the right hand track in the postcard. At the bottom of the hill, the "barney" would be pulled from the "barney pit" by the plates to a position behind the car, where it would begin to push it up the plane. The two wheels in the engine house rotated in opposite directions so that as one car was being pulled up, another was being let down. On Mt. Pisgah, they travelled at about 370' per minute.

At the centre of the postcard above is the ratcheted iron rail known as the "cat step". As a car climbed, a mechanism known as a "hold fast" dropped onto this from the "barney" to prevent the car from running back down the plane if the iron strap was to break. It made a distinctively mechanical "ratcheting" sound as the car climbed.

One of the chimney stacks of the Mt. Pisgah engine house can just be made

out at the top of the plane in the view above from The Switzerland of America. The poles holding the signal wire to the engine house run up the left side of the plane.

The cut to accommodate a set of tracks

for a ballast car runs diagonally to the right beneath the stationary car in this photo, as tests on the new railroad showed that the "barney" cars were not sufficiently heavy to prevent twisting of the iron straps as they descended the plane. The use of a ballast car, also

known as an "idling" car solved the problem.

Sited to the west of both inclines, the "idling" cars ran on their own tracks and were filled with ballast and scrap iron. A single wire cable connected the "idling" car to the rear of each "barney" via a pulley. The weight of the "idling" car then kept a constant tension on the strap connected to the "barneys" whether they were ascending or descending. A winch to tighten the cable was attached to the rear of each "barney".

Above, an information sign at the original location of the engine house shows how it once looked.

Inside, two coal burning furnaces supplied steam to the cylinders that powered large driving rods connected to cams. These turned toothed wheels geared to the 27' diameter wooden wheels that wound or unwound the iron straps as cars ascended or descended the plane. The steam engines also powered pumps to feed water to the boilers, initially drawn from the Lehigh River.

Below, a view looking south east across the ruins of the engine house. Jim Thorpe is in the valley just beyond the trees on the right.

Some time before 1862, the water source for the Mt. Pisgah engine house was changed from the long rise required from the Lehigh River to the nearby Indian Spring, a pool located about a half mile west along the grade. This fed water through earthen pipes to a wooden reservoir constructed just west of the engine house.

In 1862, the earthen pipes, which were prone to breaking, were replaced with 3" cast iron pipes.

On the left, the wooden reservoir was later replaced by a concrete one. The remains can be found just below the grade as it heads west from the engine house towards the Mt. Pisgah Trestle.

After passing through the engine house, cars continued a short distance to Mt. Pisgah Trestle.

Above, an early 20th century postcard view of the trestle from the western end. Between the engine house and eastern end, you can just make out the outlines of the water reservoir.

The wooden trestle was built in 1845 to span a shallow gully between the engine house and a ridge 475' to the west. Although a hand rail appears in this view, other pictures of the trestle reveal this was not always in place.

Above, a view looking west across the now overgrown gully from the top of the eastern abutment of Mt. Pisgah Trestle.

Above, two views of the eastern abutment from the gully floor.

One of the angled concrete piers that supported the trestle can be seen on the gully floor in the photo on the right. The trestle legs or "bents" were fastened to the piers, but it must still have been rather disconcerting to cross the gully on such a flimsy structure, particularly without a hand rail.

At the western end of the trestle, a wooden platform known as "High Point" had been built where cars stopped so that passengers could disembark and enjoy the view across Mauch Chunk valley to the township below. The stop was necessarily brief, however, if another car was on its way up the Mt. Pisgah plane, and the car would soon have to resume its gravity driven course west.

Today, like the original trestle bridge, the "High Point" wooden structure is long gone. Above, only the concrete western abutment of the trestle remains, and the grade has become largely overgrown. As a result, gone too are the once expansive views.

Just west of the Mt. Pisgah Trestle was the site of a siding and Pavilion Station.

Nothing now remains of the small, rusticated wood station shed built in 1872 located in the open area on the right in the view below.

Passengers could disembark at the station. From there, they would walk a short distance along a pebbled track, the remains of which run up from the right in the photo above, to a landscaped open area with gardens, a fountain, a refreshment pavilion, summerhouses and an observatory.

Above, the cracked conglomerate track to the site can still be easily followed.

A special closed car was provided for passengers attending moonlight dances.

After being hauled up Mt. Pisgah plane, surely a spectacular experience at night, the car was switched off onto the Pavilion siding for passengers to disembark.

Above, two views of the former location of the Pavilion facilities. Little survives except a few half buried dressed stones. Built by the LC&N in an effort to popularise the railroad and attract more tourists, they had a short life.

The gala opening on 7th July 1872 was attended by nearly three hundred guests. It commenced at 7.30 pm with a "Grand March" on the pavilion dance floor, and the celebrations went on until after daybreak. Moonlight dances were held over the next few years but, as the decade progressed, the popularity of the facilities waned. After being badly damaged in a storm in October 1878, they were abandoned by the LC&N.

From Mt. Pisgah, the back track begins a gradual, 6⅔ mile descent at about 45' per mile to the foot of the second plane at Mt. Jefferson. On the way, Hacklebernie Tunnel is just a couple of miles west of Mt. Pisgah.

Proposals to build a back track were mooted as early as 1829, when a prospective route was surveyed by Moncure Robinson. He had

already surveyed the route of the Allegheny Portage Railroad (you can see photos on the Allegheny Portage page of this website). Robinson's proposed route included a six hundred yard long double track tunnel through Sharp Mountain and was costed at $67,654.57. He argued the new route would increase tonnage from 200 tons per day to 500 and produce annual savings of $6,215.48. Unfortunately, Josiah White was already committed to inclined planes as the source of power for a back track, although he had in mind a water driven plane at Mt. Pisgah and a steam driven one at Summit Hill. For whatever reason, plans to build a back track were shelved until the 1840s.

Above, two views looking west from the eastern side of the grade overlooking Hacklebernie Tunnel.

Above, looking into the now clogged portal of Hacklebernie Tunnel.

Work started on the tunnel in 1824, decades before the back track was constructed. It was hoped the mine might provide a source of coal closer to the Lehigh than those at Summit Hill, but it was abandoned in 1827 after completion of the down track without producing any marketable coal (it had been driven 790'). With arrival of the back track, however, interest in the tunnel revived.

Above, the grade passes over Hacklebernie Tunnel.

Above, looking east along the back track just east of the Hacklebernie Tunnel.

Running up to the left is evidence of what appears to have been a short siding, possibly used for storing empty coal cars or as a turnout.

Above, two views looking east from the western side of the grade overlooking Hacklebernie Tunnel.

Above, looking west across the foot of Hacklebernie Tunnel. A railroad spur led up, roughly in the centre of this view, to connect to the back track a few hundred yards west at a point called the "Stand on the Backtrack".

Initially, loaded cars were hauled up the spur by mules and then coasted west down to Five Mile Tree where they switched onto the down track to travel east to the chutes at Mauch Chunk. They returned via Mt. Pisgah and switched back onto the spur at the "Stand".

Above, looking north from the spur at Hacklebernie Tunnel up to the old back track grade.

Above, two views where the spur joined the back track. On the left, looking west. On the right looking east.

As tunnel traffic began to interfere with operation of the back track, a separate gravity railroad was built in 1854 to connect with the down track on the "Home Stretch". This track came to be known as the "Switchback" as it used "kickback" switches at each of two "Y"s. The term caught on and eventually became synonymous with the entire LC&N system.

It's about three miles from Hacklebernie Tunnel to Five Mile Tree.

By the 1840s, competition in the coal trade had greatly depressed coal prices, with serious economic effects on the LC&N. It was in this context that White's proposed back track with its two inclined planes was revived, although

the Mt. Pisgah plane would actually be steam rather than water powered. Proposals for building the track were advertised in July

1844, and work on grading began the following month.

The LC&N Board of Directors had hoped to

have the new back track operational by the opening of the 1845 season, but this proved

over optimistic. A severe storm interrupted progress, and the Chief Engineer, Edwin Douglas encountered delays in laying the iron straps on the wooden rails, as well as installing machinery in the engine houses. The track was officially completed in August 1845 at a cost of about $115,000, but probably did not carry any cars on a regular basis until the 1846 coal season.

Above, two views looking west as the grade approaches Five Mile Tree.

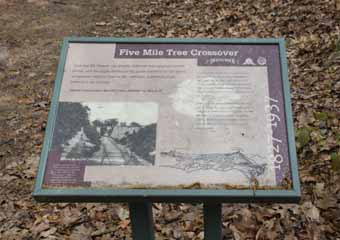

To minimise signalling at the junction of the two tracks, it was decided that cars on the back track would crossover the down track on a short bridge. This meant cars could continue unimpeded in both directions.

Above, an early 20th century postcard showing a passenger car on the back track crossover at Five Mile Tree.

The track on the left of this view allowed cars to transfer from the back track to the down track. Cars would run down to a "Y" and then forward to connect to the down track through the switch in the foreground. Moonlight Pavilion cars were switched in this way, as well as coal cars from Hacklebernie Tunnel until the "Switchback" was completed between the tunnel and the "Home Stretch" in 1854.

Above, the back track pulls away from Five Mile Tree on the left in this view looking west along both grades. The down track is on the right.

Above, another view looking west along the back track a little distance from Five Mile Tree. The down track is just out of view on the right.

Above, a view looking east back along the back track towards Five Mile Tree. The down track is clearly evident running down from the left in this view.

As indicated by the direction marker on the left, Mt. Jefferson plane is about two miles west of here.

Above, a view looking west from the back track shows the awesome profile of Mt. Jefferson about a half mile distant.

At this point, the grade becomes a little difficult to follow. It emerges onto the north east corner of the Summit Hill Catholic Church Cemetery on East White Bear Drive and re-enters a copse of trees on the far side (the view above is looking back through the trees towards the cemetery). It then all but disappears into market gardens and the yards of private residences.

When I walked the grade, I took to East White Bear Drive for a few hundred yards, bringing me right to the foot of Mt. Jefferson plane.

The foot of Mt. Jefferson plane is at the intersection of East White Bear Drive and Laurel Drive/Route 902. It is hard to miss as there is a car park there and the remains of the original "barney pit".

The pit was identified by the Summit Hill Historical Society in 1999 and bought by Bob Gormley in 2000.

Gormley intended to clear the fill, restore the pit to how it was during its operating days and build an enclosure to protect it from the weather.

The pit is now fully exposed and, eventually, strap rail will be made and installed.

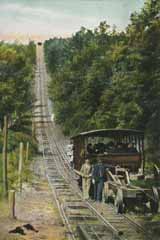

Above, an early 20th century postcard shows the "barney" rising out of the Mt. Jefferson "barney pit" to connect to a passenger car.

Above, this postcard stamped 1908 shows the "barney" at the rear of a car. The cable on the far right was connected to the "idling" car.

At 2,070', Mt. Jefferson was shorter than Mt. Pisgah. It did not rise as high either, just 464', and had less of an incline at 22%, but these shortcomings may have been overlooked by passengers as, at 740' per minute, their cars were lifted at twice the speed of Mt. Pisgah.

Soon after the back track came into regular use in 1846, the iron straps used to support the "barneys" began to break where their

30'-40' lengths had been welded together. The solution, at Josiah White's suggestion, was to overlap the welded joints on both sides with riveted iron plates, combined with using thicker, wider, better quality straps. The new straps were a success, lasting twenty years before needing replacement.

Another improvement was the installation of a second engine at each engine house. This would forestall any interruption to service if one of the engines were to fail.

As is evident in the early 20th century postcard above, Mt. Jefferson did not have a "cat step" rail.

Instead, its safety device consisted of what were called "outrigger legs". These baseball bat shaped arms were attached to the sides of the "barney" and designed to arrest any backward motion by catching the railroad ties beneath.

The "outrigger legs" did not work well, however, probably because of the poor condition of the ties, and there were several runaways on Mt. Jefferson over the years. It was fortunate no one lost their life in these.

Above, looking west up Mt. Jefferson plane from the foot.

The "barney pit" is immediately behind where this photo was taken.

Above, looking east from the foot of Mt. Jefferson plane to the "barney pit".

East White Bear Drive is just beyond the far end of the pit.

The early 20th century postcard above shows a passenger car ascending the Mt. Jefferson plane.

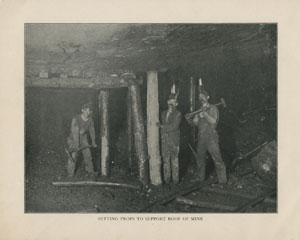

Completion of the back track allowed the LC&N to expand its coal mining activities and, as the Sharp Mountain Quarry at Summit Hill neared the end of its productive life, the company turned increasingly to its mines in Panther Valley to the north and west. By 1854, the original quarry had been abandoned and nine tunnels were in operation, supported by a complex of gravity driven railroad tracks powered by steam engines.

The coal was transported to a breaker on Summit Hill and then loaded onto cars to be carried on the down track to the Mauch Chunk chutes.

Above, a view looking west up the plane about half way between the down track crossover and the original location of the Mt. Jefferson engine house.

This part of the grade appears less frequented than the more level sections.

Half way up the plane another crossover carried the back track over the down track.

In the top photo above, a view of the remains of the western abutment. In the lower view, the eastern abutment was removed when the down track track was removed and the way widened to create East Holland St.

Left, a postcard stamped 1909 shows the view looking east from the top of Mt. Jefferson plane. The posts running down the incline on the

right carried the wire pulled by the engineer at the foot of the

plane to signal to the engine house that the car was ready to ascend.

Left, a photo taken from roughly the

same position. Mauch Chunk Watershed Lake in the middle distance below now fills much of Bloomingdale Valley.

It was created in 1972 to reduce flooding by Mauch Chunk Creek.

As with Mt. Pisgah, climbing the Mt. Jefferson plane is really only for the physically fit.

As you can see from the photos here, the path is steep, rough and strewn with rocks, but hikers are rewarded with some great views.

Above, the Summit Hill Historical Society has placed a bench at the top of the plane.

Above, only scattered stones now remain at the site of the original engine house.

The LC&N started carrying employees from Mauch Chunk to its Sharp Mountain Quarry as soon as the down track opened in 1827. This made it the first passenger railroad in the US, and it was soon allowing visitors to ride as well. But, instead of operating services itself, it contracted with private individuals to operate what became known as "pleasure carriages". The company set the fare at 25c for locals and, initially, 50c for visitors, taking half the net receipts. In 1829, the visitors' fare was raised to 75c at which level, surprisingly, it stayed until the switchback closed in 1933.

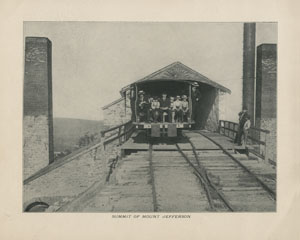

Above, "Summit of Mount Jefferson" from The Switzerland of America.

After clearing the engine house, cars passed over a short trestle as they began their descent into Summit Hill.

Above, a view looking west taken from roughly the same position as the photo from The Switzerland of America above.

In 1830, the railroad became part of a regional system from Mauch Chunk to Summit Hill, where stage coaches connected to Tamaqua. From there, the Little Schuylkill Railroad connected to the Reading Railroad and Philadelphia.

Above, a postcard dated 1910 of the engine house from the west. Note the reservoir on the left.

The cast iron stack on the right was erected when new boilers were installed in both engine houses in the early 20th Century.

Above, another photo looking west taken from roughly the same position as the postcard. The site of the original reservoir on the left is now quite overgrown.

Water was pumped to the reservoir from a source known as "Spring Cistern", a favourite swimming spot for locals, near the down track crossover on Mt. Jefferson. The pumps were powered by the engine house boilers.

Above, looking east along the back track towards the original location of the engine house.

From here, the grade ran north west for a few hundred yards and then turned west onto Rail Road Street (now East Ludlow Street).

Above, looking west further along.

Near East Ludlow St, the grade disappears into a stand of trees (on the right in the view above).

The grade originally joined what is now East Ludlow St where the path now crosses the road in the middle distance in the photo below.

Above, west along East Ludlow St.

Above, two views looking back along East Ludlow Street. The back track ran down the right hand side of the street. In the upper view, the Presbyterian Cemetery is on the left on a plot of land given to the township by the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company in 1850.

The township was entirely the product of coal. The first house was built in 1800. By the late 1820s, the settlement consisted of just five log cabins but, during the following decade, LC&N began building houses for its employees at the Sharp Mountain Quarry and Panther Valley mines and the township began to grow. Local businesses were started, including the Eagle Hotel, a general store and a foundry.

Above, looking west along East Ludlow Street to the intersection with Pine Street, which the switchback crossed on an elevated overpass known as the "Pine Street Crossing".

Above, there is an information sign, replica coal car and some remains of the original eastern abutment at the intersection now, but the overpass itself was removed in late 1937.

The township prospered during the last decades of the 19th century when as many as thirty thousand visitors would pass through on the switchback in a season. In 1889, it was separately incorporated as the town of Summit Hill. Until then, it had been part of Mauch Chunk.

Originally, the wagons used on the Mauch Chunk railroad were intended to carry 3 tons of coal but, at the suggestion of Erskine Hazard, one of the company directors, this was cut to 1.5 tons. This reduced wear on the right of way and lowered costs, as lighter strap iron could be used on the rails. The four-wheeled cars were built by LC&N labourers or contractors.

The cars were fitted with doors hinged at the top. When they reached a chute at Mauch Chunk, a projecting bar knocked the door open and released the coal. Missing from the replica car at Summit Hill is the upright lever that projected above one side of the car to operate wooden brake blocks applied to the inside tyres of the wheels. The levers were hooked together by a long rope or chain so that the brakeman could apply the brakes on the entire train, usually 6-10 cars in length.

The original rails were 18'-20' long 4" x 6" pitch-pine rails to which 14' long iron straps, roughly 1¼" wide by ¼" thick, were secured by 4" spikes or screws. The rails were wedged into grooves driven into oak sleepers laid on trenches filled with small stones. Between 1857 and 1866, the LC&N replaced the strap iron rails with 40lb-50lb cast iron T-rails.

Above, looking across West Ludlow Street (formerly Rail Road Street) to the original location of the Summit Hill depot.

Left, a postcard date stamped October 1910 showing the Summit Hill depot.

Constructed in 1872, the building housed a ticket office, as well as a refreshment area and concession stand selling switchback-related souvenirs. To the rear can be seen the "John R. Harris' Switchback Restaurant".

Left, a roughly proximate view today. The depot site is now occupied by a legal office at the front and the Vermillion Professional Building at the rear.

The wrought iron railings are the original ones shown in the postcard above.

While they fed the Mauch Chunk chutes, a spur ran from the depot so that empty coal cars could be sent to the Panther Valley mines.

The spur ran west along what is now West Ludlow Street in front of the fire station in the photo

above.

The down track curved from the depot across what is now a play area to emerge roughly around the corner of the white house in the photo above to begin its descent along what is now West Holland Street.

As late as 1875, there was no street in this part of Summit Hill, although a few houses faced onto what was then called Rail Road Street here.

Above, looking east along the course of the down track on East Holland Street.

Pine Street is at the stop sign.

Above, looking west back along East Holland Street.

Somewhere along here, loaded cars

from the Panther mines joined the down track.

Above, looking west from the intersection of East Holland and Pine Streets.

A coal breaker was sited south of here.

Above, looking east along East Holland St at the edge of town.

Cars from the Summit Hill coal breaker were switched onto the down track near this point from the right.

Above, a postcard stamped July 1907 showing two cars at the Mt. Jefferson crossover. The lower passenger car is on what is now East Holland Street. As at the Five Mile Tree crossover, passengers in the passing cars might exchange a few brief words of conversation.

From the outskirts of Summit Hill, the down track went through an elongated S curve for just over a mile along the flank of Mt. Jefferson and onto the northern side of Bloomingdale Valley, so that it maintained a relatively uniform drop. The crossover is roughly at the central bar of the S.

Above, there is an information sign just to the south of the old crossover.

Above, looking back up the down track through what was once the Mt. Jefferson crossover. The surviving abutment is on the right hand side of the road. The information sign stands in front of the heap of rubble at the centre of the photo.

At 96' per mile, the down track descent was steeper than on the back track. The average speed on the nine mile trip down to Mauch Chunk was 27 mph, and it took about twenty minutes, although this depended on whether the passenger cars had to switch onto a turnout to allow any coal cars to pass.

Above, Stoney Lonesome, a short section of road at the end of East Holland St. This part of the grade was known as Griffith Curve.

The three steel uprights prevent motor cars from entering the switchback trail.

Above top, an early 20th century postcard showing a passenger car on the down track at Five Mile Tree. The photo above looking east is taken from roughly the same viewpoint as the postcard.

Milepost markers were nailed to trees along the route. The crossover was roughly five miles from Mauch Chunk, and a marker with "Five Miles" was nailed to a large tree here, which gave the location its name.

Above, two views of the remains of the original crossover abutments. They were built from

local stone and are remarkably well preserved. The top view is looking east along the down track as it heads to Mauch Chunk. The lower view is looking west back up the down track towards Summit. The back track approaches to the top of the abutments on both sides of the crossover are now quite overgrown and inaccessible.

Originally bearing a trestle bridge, the

crossover was later rebuilt with the stone abutments on which heavy wooden planks were set. The rails were then laid at an angle across these.

Above, looking east from Five Mile Tree.

Above, looking west back along the grade to the remains of the crossover.

After rebuilding the deteriorating route in 1848 to remove some tight curves, from here the down track travelled in an almost straight line to the "Home Stretch".

Above, the Pennsylvania Historical and

Museum Commission has erected an historical marker on the north side of the Lentz Trail Highway where the down track crossed the road. It is about a mile west on the grade from Five Mile Tree.

The original rails remained on the highway for many years after the switchback was abandoned as a mute reminder of its previous existence. They were finally lifted some time in the 1950s.

Today, the crossing is at the main entrance to Mauch Chunk Lake Park.

The main information sign positioned here has a brief history of the railroad, an

outline of a walker's tour and an aerial impression of the entire switchback.

It also has some interesting historic photos of parts of the switchback.

Above and above right, just east of the park entrance there are some information signs, and a replica passenger car.

Initially, the LC&N installed seats in coal wagons, with a canopy supported by poles to protect passengers from the weather. Later, purpose built cars like this replica were used. They seated about eight passengers but, as the switchback became more popular, larger, more elaborate cars were added of the kind shown earlier on this page on the Mt. Jefferson crossover.

Right, it is just a few hundred yards along the down track from the replica car to the Mauch Chunk Watershed Lake.

The lake was created in 1972 to reduce flooding by Mauch Chunk Creek, and it had a major impact on the local economy.

The old down track grade ran straight across from this side of the lake in the photo above.

Before the lake was created, some of the

original grade had already been claimed by private owners, and increasing land values because of the new lake park placed even more at risk. The grade actually remained the

property of what had been the LC&N through Blue Ridge Real Estate, a subsidiary of LC&N's successor, the Lehigh Navigation Coal Company. Still, from the 1970s, interest in preserving the grade grew, stimulated by publication of the The Valley Gazette, its monthly editions often featuring historical photos and articles on the switchback.

The "Switchback Scamper" also stimulated interest. Initiated by Ed Gildea, editor of the Lehighton Times News and Valley Gazette, in 1971, this run on the down grade from Summit Hill to Five Mile Tree and back to the top of Mt. Pisgah was to become an annual event. Meanwhile pressure mounted on the LC&N to donate the entire grade to Carbon County.

Below, looking west at the breast of the Mauch Chunk Watershed Lake dam. The grade originally ran from the trees on the other side of the lake to the left of this view.

Above, a view west back along the grade towards the lake.

The first part of the trail was donated by the LC&N to Carbon County in 1973 and the rest in 1976, when the trail was also placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

From about a mile

and a half east of Five Mile Tree, Mauch Chunk Creek ran close to the grade on the southern side of the down track.

The creek is hidden

by trees and bushes just to the right in the view looking east above.

Above, looking west back along the grade after crossing Mauch Chunk Creek.

In 1980, the entire switchback route was designated a National Historic Recreation Trail. Six years later, the Switchback Gravity Railroad Foundation was established to investigate the feasibility of developing the route. Various plans were considered to restore the railroad to operating condition but the funding proved elusive over the next decade and a half, and there was opposition to the plans by some local landowners.

Above, looking east along the down track at the start of what was known as the "Home Stretch" about two and a half miles from Five Mile Tree.

It was about here that cars loaded with coal from the Hacklebernie Tunnel mine were switched onto the down track (from the left in the view of the grade above) after crossing Mauch Chunk Creek on "Board Bottom Bridge". The creek is on the left.

As the name implied, this was the start of the last section of the down track, although it appears there was never a sign post or official point at which it began.

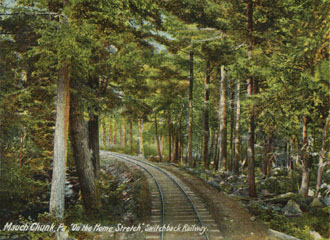

Above, an early 20th century view looking west of a passenger car on the "Home Stretch".

Above, a roughly equivalent view today.

The switchback's first season as a passenger only operation was a great success, and the next was even better: 30,478 people paid the 40c one way or 75c return fare between April and November 1873. At the same time, a whole industry was spawned to promote the railroad to potential visitors. Stereo slides, photographs, engraved views and even items carved from the local coal were available to buy at hotels, stations and souvenir outlets in Mauch Chunk and Summit Hill. From the early 20th Century, postcards

and souvenir booklets like those reproduced on this page also appeared.

Above, another early 20th century postcard view of the "Home Stretch".

Above, a photo taken at roughly the same spot as the postcard. Both views are looking east and Mauch Chunk Creek is on the left.

Storm clouds were looming, however. Already lumbered with a heavy debt from the extension of the Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad, a sudden economic downturn in the Fall of 1873 pushed the Lehigh Canal & Navigation Company towards financial collapse. In December of that year, it was forced to sell or lease all its properties to the Central Railroad of New Jersey, except the Nesquehoning Tunnel and the switchback.

Above, looking west along the grade at "Two Mile Turn". Usually announced by the conductor, this part of the down track signalled there were only a few minutes of travel left to Mauch Chunk.

In June 1874, CNJ

bought the switchback's rails, ties, equipment

and buildings for $75,242.12, although ownership of the grade remained with the LC&N. It appears CNJ intended to strip the switchback, but it was soon clear that doing so would greatly reduce income from tourist traffic on its newly leased Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad. In November, the switchback grade was therefore leased from LC&N for the nominal sum of $1.00 pa.

Above, a little on from "Two Mile Turn", the grade re-crosses the Lentz Trail Highway.

From the Lentz Trail Highway, Flagstaff Road climbs back up Flagstaff Mountain (on the right in the view above).

In 1902, a trolley car service started connecting Mauch Chunk over the mountain with Lehighton. With its panoramic views of the town, Lehigh River and Bear Mountain below, the trolley operators soon realised this might be a major attraction in its own right and, the following year, Flagstaff Park was opened with a pavilion, lookout and picnic grounds. During the season, concession stands also operated.

Above, the original concrete steps at the trolley interchange still survive on the north side of the Lentz Trail Highway.

The trolley section between Lehighton and Flagstaff Park was abandoned in 1925, and the remainder in 1930.

Above right, the grade crossed the Mauch Chunk Creek just beyond the trolley stop.

Above, although it's not marked on maps.google.com or mapquest, after crossing Mauch Chunk Creek, the grade runs along a private road just off West Broadway (the continuation of the Lentz Trail Highway).

From here, the down track hugged the side of the hills above Mauch Chunk.

Parts of the old stone turnpike can be glimpsed among the trees. Above, the remains of an old culvert.

CNJ leased the railroad to the proprietor of the Mansion House Hotel and two brothers, Theodore and Henry Mumford, in 1879. The Mumford brothers then renewed the lease in 1880 for an annual fee of $1,000. Despite a legal dispute with the Reading & Philadelphia Railroad, which took a lease on the CNJ in 1883, the Mumfords managed the switchback until their lease ended in 1899.

Except for a dip in the mid 1870s, 1872-1899 were boom years for the switchback. In October 1893, over 6,000 visitors arrived at Mauch Chunk in just one day and, by the close of the decade, the switchback was carrying over 100,000 passengers a year.

In 1899, the lease was sold to the brothers Alonzo and Asa Packer Blakslee for a period of ten years. One third of gross receipts were to be paid, with a minimum of $2,400 pa. However, the brothers were soon facing competition from Flagstaff Park. From 1903, both visitors and locals increasingly chose the park over the switchback, which did not offer picnic facilities or dancing.

Above, as it neared

the depot, the down track curved around the southern

boundary of the Mauch Chunk Cemetery.

The trees on the left

in these two photos now obscure what

was considered one

of the finest views looking down the steep hillside to the township below.

Below, from the cemetery, the grade makes another curve and then descends a short straight section before arriving at the site of the Mauch Chunk depot.

Above, a view looking east across the site of the original depot. This view is taken from the south side of where the shed stood that was used to board passengers at weekends and on public holidays.

The ticket office was where the white shed in the middle distance now stands and the "Switch Back Restaurant" was located until 1909/10 on the same ground as that now occupied by the white house in the distance.

Below, looking back along the grade from where the passenger shed stood.

Above, a view looking east along the grade to Packer Hill.

After disembarking at the depot, passengers would make their way back down the hill either by foot, trolley car or in horse drawn coaches.

Above, looking down Packer Hill from the grade. The wrought iron railings on the left survive from the period when the switchback operated.

From the early 1900s, the switchback's fortunes began a steady decline. Passenger numbers dropped and the frequency of services was reduced from eight to five a day. Troop movements during WWI greatly disrupted excursions, and opening of the 1919 season was delayed because of equipment failures and the poor condition of the railroad.

During the 1920s, Mauch Chunk struggled to accommodate the increasing volume of car traffic. Roads into town were unsuitable and there was limited parking. Profits steadily fell and the switchback posted a loss in 1928, before returning to profit in 1929. The railroad was purchased from CNJ that year by a group of local investors for $9,000, but equipment failures, accidents and financial difficulties dogged the railroad, which posted losses in the following years. Finally, services were quietly abandoned after the last run on 29th October 1933.

For the next four years, attempts to resuscitate the switchback stuttered on but it was impossible. On 2nd September 1937, the railroad was sold at auction for $18,100.

Related Links:

Switchback Gravity Railroad Foundation

Mauch Chunk, Summit Hill, and Switchback Gravity Railroad

Historic Look at Summit Hill

Send a comment or query, or request permission to re-use an image.

The great majority of the historical information on this page is from Vincent Hydro's The Mauch Chunk Switchback, published by the National Canal Museum in 2002 (click on the cover to search for this book on Bookfinder.com).

Arcadia Press also published Jim Thorpe by John Drury and Joan Gilbert in 2001 and Summit Hill by Lee Mantz in 2009 as part of the "Images of America" series (click on the cover to search for either book on Bookfinder.com).